Genesis (1299 to 1869)

Singapore’s emergence as a great 14th century port is recorded through the stories of the Malay Annals, which accords 14th century Temasek or Singapura with the status of the first great port of the Malay world. There is little doubt of Singapore’s place in the region’s rich maritime history. A large body of archeological evidence does show that Singapore was indeed a thriving centre of trade and exchange.

Temasek’s rise would have had much to do with its advantageous geographical position at the crossroads of ancient maritime trading routes. This made it perfectly placed to benefit from the growing appetite for Chinese ceramic and silks in the West and in the Middle East, and for Middle-Eastern aromatics in the Far East. The region’s forest and waters were also fertile as sources of items in great demand such as lakawood for incense, hornbill casques – an ivory substitute, and the highly-prized trepang (sea cucumber).

In spite of its advanteges, Singapore’s golden age of the Malay Annals was short-lived; its fortunes flowing and ebbing like the tides that carried its prosperity in. Singapura’s vulnerability to external events such as regional conflicts left its exposed. Power struggles, climatic disruptions, and eventually changes in trading patterns had an impact and an abrupt end was brought to this first recorded age of glory with Singapura fading into relative obscurity.

Singapura seemed to have reemerged in the 16th century as an outpost of the ascendant Johor Sultanate, during a time when hitherto unseen threats made their appearance. The European powers had entered the fray and while Singapura may not have attained the same status as it did in the 14th century, its presence did not go unnoticed. From Dutch and Portuguese texts and charts, we learn of Singapore’s emergence as a “Xabandaria” or “Sabandaria” – a shahbandar’s or harbourmaster’s station. Fragments of 16th century fine Chinese ceramics uncovered in the Kallang River estuary, point to Singapore also being a centre of exchange at the time.

Flemish trader, Jacques de Coutre, went as far as identifying the Xabandaria’s potential as a defensive outpost early in the 17th century. Singapura however remained largely ignored by the Europeans, serving as the Orang Laut Raja Negara’s base until the 1770s.

By the time of the 1819 arrival of the Honourable East India Company (HEIC), Singapura had gone off the radar once again. The arrival of the HEIC to establish its emporium and free port on the island, could be thought of as having launched Singapore’s modern era.

One of the successes of the HEIC’s free port in Singapore, was its ability to draw human capital in. This went beyond the hands and legs that were needed and encouraged the coming together of diverse cultures, the flowering of ideas, and with it, the growth in intellectual capital. Singapore’s capacity for interaction and exchange provided a competitive edge and an ability to adapt to the technological developments of the day. The world was on the cusp of a wave of globalisation, and Singapore stood to regain its position as as great regional port.

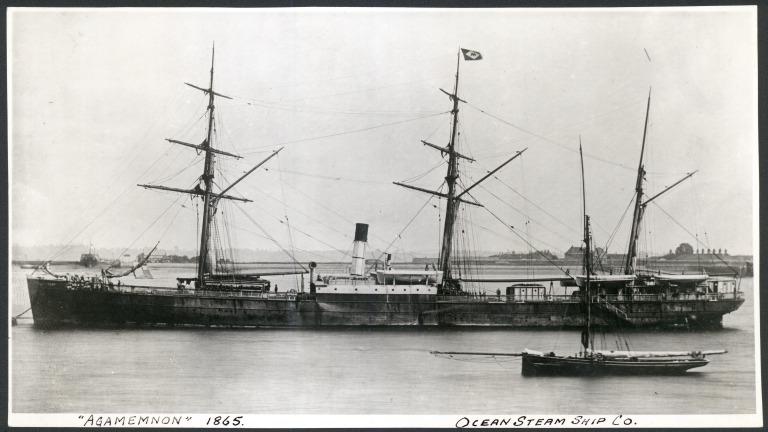

The building of New Harbour’s first wharves in the 1850s would be a turning point for Singapore. Erected by the Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Company (P&O) at Tebing Tinggi to service their steamers, they set the development of New Harbour in motion. P&O’s steamers carried the mail. Moved through the Mediterranean, then overland to the Red Sea, and then across to the subcontinent, mail made the last leg of its journey to Singapore by steamer from India. The first steamers to be seen here were slow and cumbersome. Highly inefficient, they also had a huge thirst for coal. Coaling was a long and tedious effort. Initially, coal was stored upriver and carried by barge or lighter to steamships at anchor. The construction of deepwater wharves at New Harbour made the still labour intensive process a lot more efficient.

Photograph: Rijksmuseum (Public Domain)

The use of steam to power ships at this point had still a long way to go. Steamships could not compete with fuel-free wind powered ships. Steamships of the day carried sails for this reason, with steam machinery providing only the advantage of some measure of certainty in scheduling. Sailing ships still carried much of the world’s cargo. The installation of steam machinery sacrificed valuable volume. It wasn’t just that of ship’s hold for the engines, but also the volume to carry a sufficient quantity of coal to move the ship to its next coaling station.

While the adoption of the screw propeller obtained improvements in propulsive efficiency and a reduction in coal consumption, it would take much more to see the age of the steamship take off. Advances made in steel processing for example, made the high strength material more affordable. Its usefulness was not just in making ships longer and lighter, but also in permitting steam to be produced at higher pressures. Ultimately, it was Alfred Holt’s introduction of a highly-efficient compound steam engine in the mid-1860s, which could cut coal consumption by half, coupled with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 that would do the trick. The passage through the canal and the Red Sea passage made the steam powered ship a necessity due to the opposing wind conditions that would be encountered.

Investment in wharfage, coaling sheds and graving facilities through the 1850s and 1860s by New Harbour Dock Company and Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, meant that Singapore was in an excellent position as the new generation of ships multiplied. Already a main naval coaling station for the British and French naval fleets involved in their respective thrusts into the Pearl River delta and Indochina, Singapore became an key coal bunker station for the growing merchant fleet supporting the China and India trade. Singapore was set on its way to becoming one of the world’s principal ports, a position that it still holds today.

(To be continued)